In the latest instalment of “Mick talks with..”, I sit down with strength and conditioning expert Lachlan Wilmot to discuss all things plyometrics. For those of you that don’t know Lachlan, he is the co-owner of the private athletic performance facility in Sydney called Athletes Authority. Lachlan has also spent a decade in professional sport working with the Parramatta Eels Rugby League team and the GWS Giants AFL club. I hope you all enjoy our chat, and learn as much as what I did!!

Mick: Thanks for your time Lachy. I'll start with a simple one first; what is a plyometric exercise and can you give us a typical example?

Lachlan: In its purest form, a plyometric exercise is an exercise that is substantially low on ground contact time. It's an aggressive movement; and if you had a really simple way to define it, and this is the way I like to define it for a lot of coaches, is that if you're using more tendon during the exercise, it’s plyometric. If you're using more muscle, then it's probably not going to be plyometric. Your muscles simply can't contract fast enough to utilize a high-end plyometric movement. So, something like a depth jump or a three-hop for distance that has very short contact times, that's a true plyometric. Things like a box jump – technically that is not a plyometric exercise. It doesn't actually have ground contact time, it doesn't have the same elastic properties as a continuous jump does.

Mick: I read once that you shouldn't do plyometrics until you can squat 1.5 times body weight. Is this true, or is it a piece of research taken out of context?

Lachlan: It's certainly out of context, but it's not false. The concept behind this is, if you think of something like a shock method plyometric exercise like a depth jump or a single leg three-hop for distance, it takes a lot of force for a tendon to accept and produce this force and is a very high eccentric load through muscles.

So If you aren't strong, you're going be shown up, and you’re likely to get sore or injured. Simple as that.

For me though, just because you can't squat 1.5 times your body weight, doesn't mean you can't do plyometric training. But what it would mean is that, you're likely going be further down the continuum than someone who can squat it. So, in very simple terms, I don't think you need to have this target of 1.5 times body weight, but it will certainly work in your favour if you can.

Mick: Very good. So in this day and age, everyone wants to be faster, bigger, stronger. But there's no point being faster, bigger, stronger if you don't know how to slow down. How important is landing and deceleration training in plyometrics?

Lachlan: Massively. There's no point being able to speed up if you can't slow down. I love deceleration work.

People underestimate how much deceleration contributes to change of direction. If you can't decelerate well, your change of direction will be pathetic. And if you've got poor yielding forces, I think it puts athletes at risk of ACL injury via valgus collapse, as their hip and knee can’t cope with the high forces placed upon it when trying to stop suddenly and/or change of direction causing them to drop inwards at the hip and the knee.

So, to answer your question, I'm a massive believer in deceleration work and eccentric absorption work, and that's why its such a big part of the plyometric continuum.

Mick: Nice one, so I’ve read that rest between sets is important when doing plyometrics because you want high quality efforts each set. Are there any guidelines in regards to how much rest between sets you should have when doing plyometric programming?

Lachlan: There's certainly a couple of papers, and there's also a couple of books out there that try to define the best rest periods. But most of the time it really does depend on the athlete and the sport such as training age of the athlete and their exposure to plyometrics. For example, If I'm working with an athlete that hasn't done much plyometric training, I'm naturally going to use lower amplitude plyometrics such as skipping, pogo hops or tall to short landings. So really low-level work; and for these athletes my rest periods are much less because you're not taxing the tendons the same, they don't require the same recovery (eg. 30-60seconds). So when I have an athlete with more experience and their training age starts to grow, I'll move them down the plyometric continuum to do bigger movements such as depth jumps or triple leg hop for distance. Therefore, their system's being taxed more, they have the ability to produce more power, and their rest time starts to grow and grow and grow (for as long as 2-3mins). In summary, I think low amplitude plyometrics and those earlier in their stage of athletic development, who are doing low level work, you can have shorter rest periods. The more advanced they get, the more intense that plyometric training gets, the longer the rest period has to get.

Mick: And then what about per week, should there be a maximum of plyometric sessions per week performed?

Lachlan: It probably ties in exactly in the same fashion of what we just discussed - where the athlete is in the early stage, doing low amplitude basic exercises; they could be done every day of the week. As we start to grow, into exercises like box jumps; because there's no eccentric load on them, you can probably get away with that three times a week. Moving down the continuum into something like a three hop for distance, with much intensity and much more a load on the tendons, I'd look to program that only one to two times a week.

So, it also depends pre-season versus in-season. In-season, most of the time with my team, I'll only get the opportunity to hit them once per week. But when it comes to pre-season, especially in the AFL when my role was that strength and power coach, we used to do three days a week, but each day was somewhat different in nature. For example, one day we would do a little bit more linear work, the next session would be more vertical work, and the next session would be more change of direction. So although they were getting that loading across three days per week, it certainly was a slightly different style of loading. An important take-home message with plyometrics is that when you start to get more serious with plyometrics like depth jumps and single leg hops for distance, it’s important to have 48 to 72 hours off between sessions otherwise you can quickly get injured.

Mick: Great stuff! You’ve touched on it during our chat so far, but can you take me through the plyometric continuum that you have developed?

Lachlan: Absolutely! It's certainly not something that I have magically invented, nor is it ground-breaking. All it is, is a systematic way to take someone through plyometric training safely with the end goal of improved sporting and athletic performance. To me, the plyometric continuum is something that I find works best for my brain - and hopefully it helps other people out.

Essentially it’s a five stage progressive model. The first phase is eccentric absorption, where you’re thinking to absorb the forces of the body. For me, it’s very important to teach the athlete/patient that in order to speed up, you've going to know how to slow down. Examples of training drills in this stage are “tall to short lands” and “altitude lands”.

The next stage is in the continuum is concentric development. So teaching someone how to actually produce force and produce power. So things like a squat jump or a sit to box jump are examples in this stage.

The next stage is called jump integration, and with the jump integration stage we start to tie the first 2 stages of landing and jumping together. In this stage, exercises that would be considered are broad jump or a single hurdle jump.

Then we move into a continuous jump stage, which is the fourth stage of the continuum. So things like a mini-hurdle hop or a continuous hurdle hop are good examples where the athlete/patient not only has to jump and absorb a landing, they have to then produce it again and again.

The last stage in the continuum is called the “shock method”; which I think only a few people have heard about. For me shock method is where you're really creating a highly aggressive jumping and landing, which creates a big impact on the joint and tendons. So things like a depth jump or a single leg three hop for distance are perfect examples of this.

Now, within those five stages there's a thousand different exercises that people can use and add to it. But the idea is to create a system, and you add whatever exercises to that system that suits you and the athlete you’re working with. For example, if you're working with ice hockey versus a track and field athlete, the plyometrics you’re going to do are going to be quite different. For an ice hockey player you'll probably have a lot more lateral plyometric work in there, whereas a 100/200m sprinter, you’ll have more horizontal or vertical plyometric movements in there.

Mick: I love it! It's very sensible. It starts low and increases complexity over time, and for my brain, it works really well too, so thank you! So in regards to where plyometrics should sit within a training session - is there an ideal time? I've been taught that they should sit at the start of the session when you're fresh so you're getting the most out of your neuromuscular system.

Lachlan: Yes and no. For me, you can put plyometrics anywhere you want. Unfortunately it's all contextual, and I think that's everyone's most hated answer. But I've put them in everywhere. Like if you're in grassroots sports, for example, working with under 14s and 15s, where they don't even get to be in the gym – I would start to use exercises in stages 1-3 on the continuum as a movement prep/warmup to their field work.

In saying that though, I would never put plyometrics at the end of a big weights session or a big field session. I think the athletes are just too fatigued, and you wont get any benefit of doing them.

Unfortunately, I know this doesn’t answer your question exactly, but it's going to be very individual. Overall, my opinion would be, everyone should try and get some plyometrics into their week somehow. But realise, that if you can only get little things like Pogo jumps into the training week, that's better than nothing. Don't think, "Oh, I can't get big continuous jumps in” or “I don't have plyometric boxes, so I can’t do plyometrics”. Keep it basic, keep it simple. Even if you do stages 1-3 of the continuum as part of a warm-up, that's much better than doing nothing at all.

Mick: Very good. Thinking ACL injury prevention for a second, rather than the performance benefits of plyometrics, do you see any value of doing landing drills or plyometrics at the end of a training session?

Lachlan: Look, at the end of the day, you’re never going to find research that's so perfect to your scenario that you can just tick it off and say “this is exactly my population and it's proved everything”. There is however research out there that shows skill acquisition under fatigue can improve it. So, for me, I think if you can minimize potential of injury, definitely I think it's massive benefit to it. So when you're talking landings at the end of a session such as “tall to short landings”, I think that'll be fantastic, and I'd have no issues with that. However, if you're doing three-hop for distance at the end of a big session, that's very different, and I would not see the value of doing something like that.

Mick: Nice one. Now I see a lot of injury recurrences soon after someone has returned back to sport; and my gut often tells me that they haven't completed their rehab properly. So in regards to rehab, how important are plyometrics as part of a comprehensive rehab plan?

Lachlan: Very important! I actually believe plyometric training is more effective for injury prevention and rehab than it is actually for performance. And specifically for injury rehabilitation, this is where the plyometric continuum works so well. Take an athlete with anterior knee pain for example. I often get asked this question, "When do you start plyometrics?” and I always respond “the time is now."

Start anything you can, as early as you can. It doesn't have to be a depth jumps. It could be as simple as Pogo jumps or skipping. It could be as simple as explosive calf pushes with a band. Just sitting there and pushing, getting some sort of elastic movement to the lower limb tendons so they get used to being under stretch before they have to produce force again.

I think people sometimes delay plyometrics because they’re worried that they are advanced, and it’s true for the aggressive stage four and five plyometric exercises on the continuum, but on the continuum, you can start at level zero and just introduce them as early as the injury tolerates them. So, for me as soon as the physio says they’re improving and getting stronger, I'm getting them to do something, it can be as simple as pogos. Then we build up skipping, and we continue to build up as their rehabilitation progresses.

Mick: Great, alright last question mate. Can you give some simple advice to anyone out there before commencing a plyometric program?

Lachlan: I think slow cook it. Take it very steady. If it means that you start with one set of two, so be it. You've just got to start somewhere. Because at the end of the day, in 12 weeks time, or in 18 weeks of your program, you want to be better than where you’re at today. By jumping into six sets of ten depth jumps, you’re going to be too sore to do anything consistently and you’re not going to get better.

Basically, I would always prefer to undershoot my first couple of weeks of programming with plyometrics rather than go the other way. Feel like it's easy, and you're dominating because in three to four weeks-time, you’ll be adding and adding to the program, and trust me, you'll find the limit of your ability.

Mick: Nice one Lachy, that's me done mate, so thank you very much for your time, wisdom and expertise!

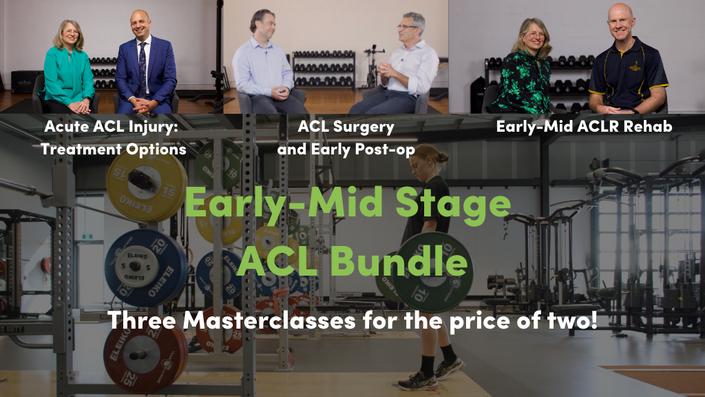

Check out our Masterclasses

Did you enjoy this blog? Enrol in one of our Masterclasses to learn more!